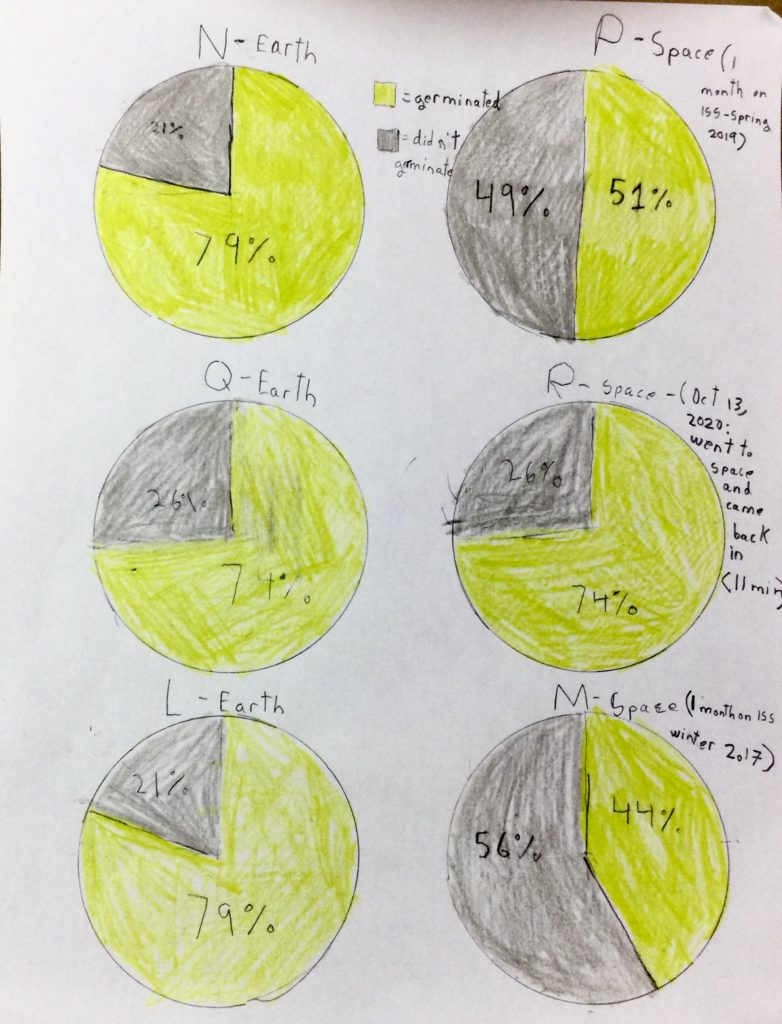

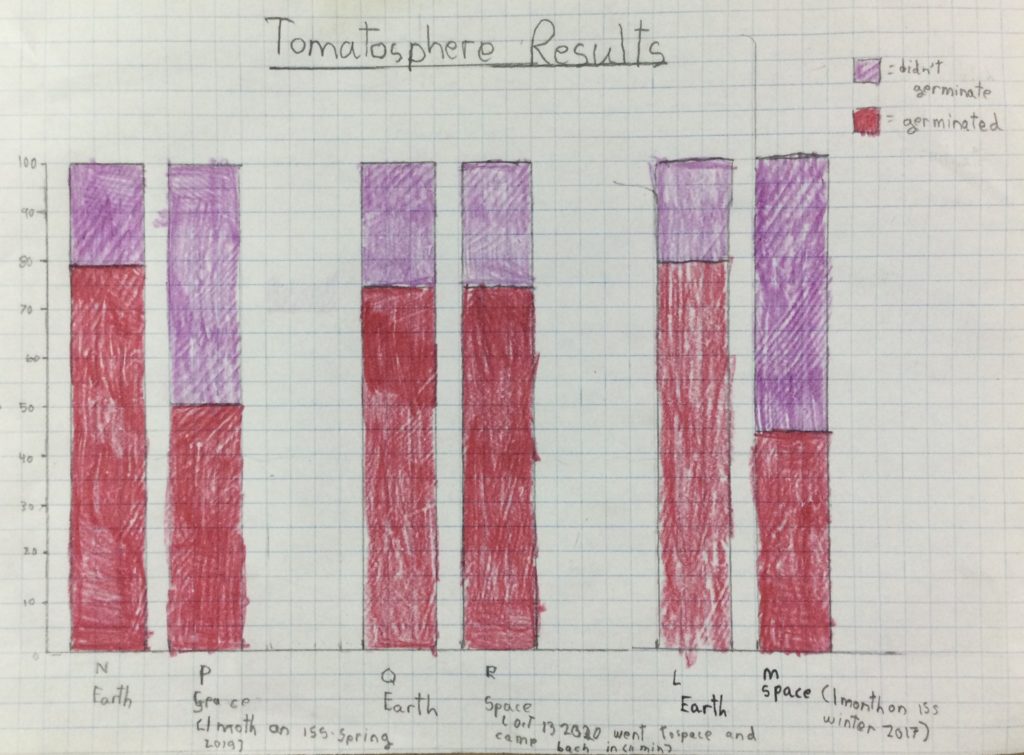

What happens to a tomato seed if it goes to outer space? Will it still germinate back here on Earth? These were the questions posed to students by the McGill Let’s Talk Science team. My daughter, and myself to be honest, were over-the-moon excited to have in our hands two seeds that had spent a month on the International Space Station (ISS) in the Spring of 2019. We were also sent two tomato seeds that had stayed here on Earth. We didn’t know which seeds were which (two seeds were in a little bag labelled ‘N’, and the other two were in a little bag labelled ‘P’). The students made their predictions, and then planted their seeds in two different pots (one labelled ‘N’ and the other ‘P’), gave them the same amount of water, and kept them in the same sunny spot. After a few weeks the students were sent to the Tomatosphere site to enter their results, to find out which were the space seeds, and to see the cumulative results!

It turned out that the ‘P’ seeds were the space seeds, and that overall those had a lower percentage germination compared to the ones that stayed here on Earth. However, my daughter’s individual results differed, and her seed that did the best was actually a space seed. That was a nice little lesson in itself on why scientists don’t make conclusions based on one data point.

There were two other similar experiments conducted with some (‘R’) seeds that made a quick flight to space and back in 11 mins, and another set of seeds (‘M’) that spent a month on the ISS in the Winter of 2017. I helped my daughter to graph the results in a couple of ways:

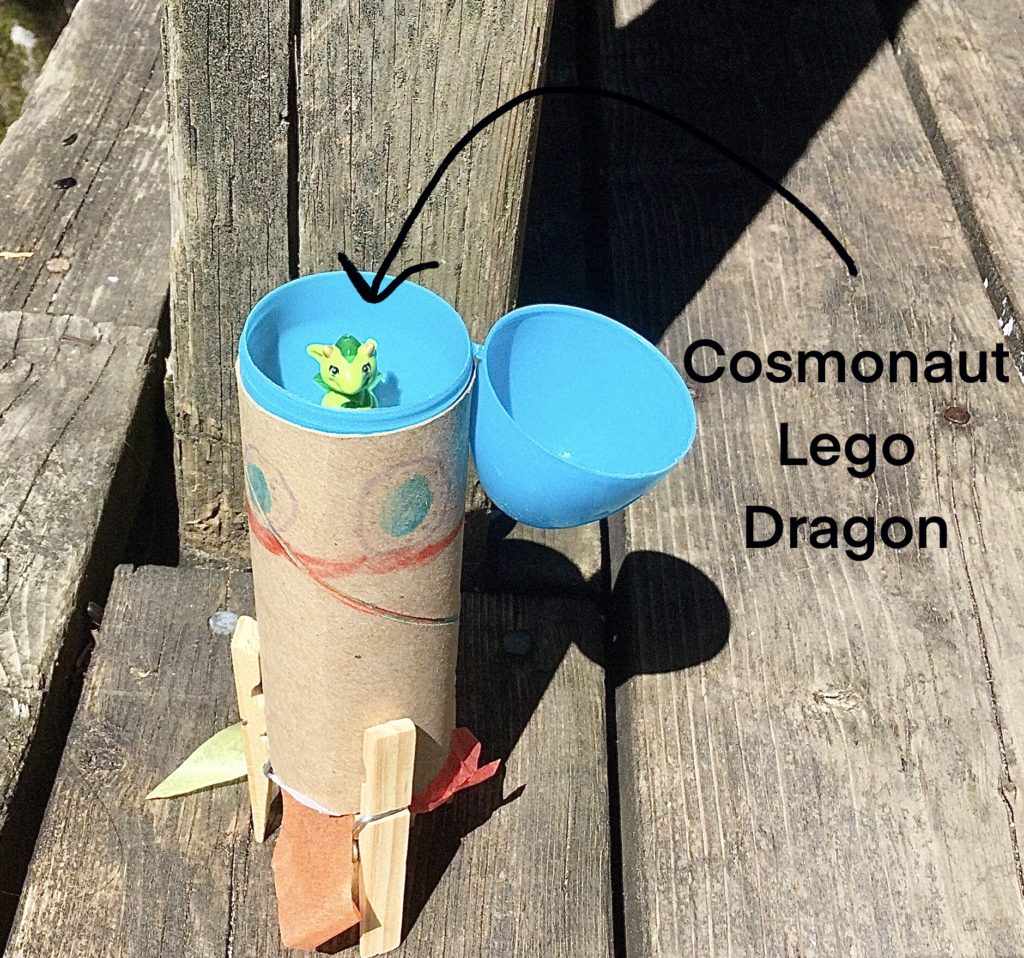

The McGill Let’s Talk Science Team also gave the students a design challenge to design a lander that would protect its instrumentation on landing.

They also made a couple of rocket ships (one shown below).

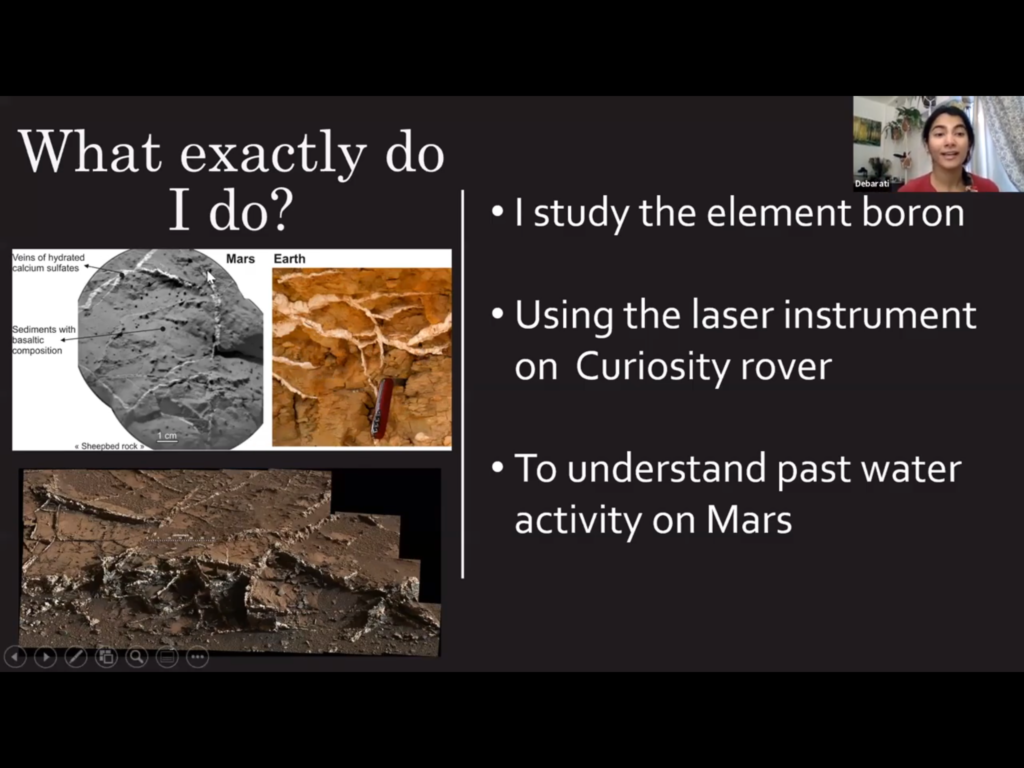

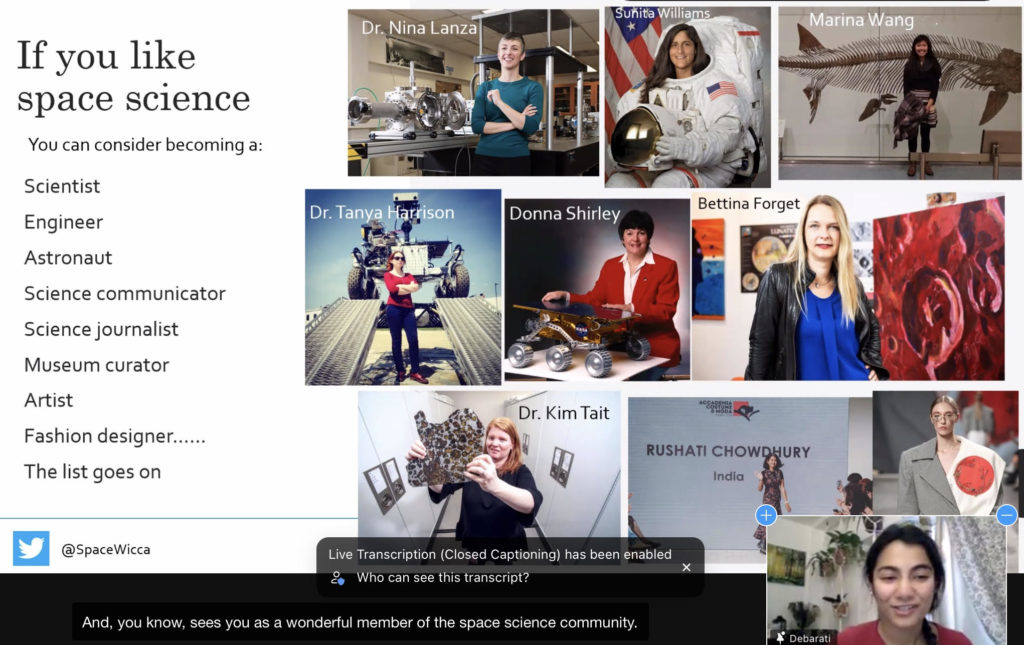

On the last class there was a presentation by Debarati Das, a graduate student at McGill University/a Planetary Geologist, a member of the NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory team, and National Geographic Explorer. She talked about her path to becoming a scientist, and about her work studying boron to help understand past water activity in Gale crater on Mars (using data from the Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) instrument on the ChemCham suite of the Curiosity Martian rover).

It was a great and interesting presentation, and Debarati was effective in helping dispel the myths or preconceptions that scientists are not good communicators, that scientist are males in white lab coats with crazy gray hair, and that scientist are one-dimensional without other interests. She, and the other grad students, were authentic and honest in answering questions. They were open about how a path in scientific research is often about what opportunities are presented and/or available, and also about some of the highs and lows of academia.

You can find Debarati on twitter @SpaceWicca, and view her presentation below:

A big thank-you to the McGill Let’s Talk Science team and Debarati Das for this fun and interesting program. My daughter was really captivated. I mean the students got to grow seeds that had been the International Space Station, and to listen to a scientist involved in real space research! So cool!

Now the question remains: How will the tomatoes taste?

Stay curious, Kate